Ground-breaking Technique for Knee and Hip Surgery

A surgical robot, perhaps a little alarmingly given the pelagic name “Mako”, is delivering stellar results for patients having hip and knee surgery. It’s likely to revolutionise orthopaedic surgery in the coming years.

The robotic ‘arm-assisted surgery’ offered by the Mako is indeed a ground-breaking piece of robotic technology. However, it’s the results for patients that are really interesting our team. Judging by some of the results from some very well-structured trials[i] (especially one suggesting the system benefits more active patients[ii]), the results are well worth sharing.

Historically, if a knee was injured and needed repairing, perhaps from an injury like a meniscus or ligament tear, or from disease such as osteoarthritis, a consultant orthopaedic surgeon may at some point be tasked with surgery. Once injury sets in the wear on the knee joint is hugely dependent upon the exact type and location of the problem, so the surgeon needs to be able to adapt to many different factors to be able to help. That’s not without risks for the patient and can often be highly dependent upon the skill of the surgeon.

Knee Surgery and The Law of Diminishing Returns

Sadly, there’s a law of diminishing returns with knee surgery – the knee can only be repaired so many times before the outcome will be a partial or total knee replacement.

A total knee replacement, as the name suggests, involves replacing worn-out knee joint surfaces with metal and plastic components. A surgeon places a metal end onto the femur (the thighbone), which connects to a metal and plastic receptor on the tibia (the shinbone).

However, in the real world, knees don’t always wear out evenly and sometimes one section of a knee joint can be completely healthy, whilst another part may be hugely degraded. Much as with a tooth (you wouldn’t necessarily wish to replace an entire tooth because of a small cavity) there’s a big question about the need to replace an entire knee if it’s partially damaged.

However, in the real world, knees don’t always wear out evenly and sometimes one section of a knee joint can be completely healthy, whilst another part may be hugely degraded. Much as with a tooth (you wouldn’t necessarily wish to replace an entire tooth because of a small cavity) there’s a big question about the need to replace an entire knee if it’s partially damaged.

A partial knee replacement involves removing and resurfacing the damaged section of the joint and leaving as much of the joint alone as possible. To be successful, the replacement components must be placed extremely accurately, to ensure the best possible fit. Even a small degree of rotation or pitch will dramatically affect the longevity of the replacement – just as car wheels need to be aligned to prevent rapid or uneven tyre wear.

Many surgeons have historically encouraged patients to delay knee surgery, often because partial knee replacements have been so tricky. That means many patients have waited until a knee condition degrades to the point that a total knee replacement is the best course of action. That matters though, because a patient is unlikely ever to kneel easily again following a total knee replacement; the range of motion is always significantly limited following the surgery.

Knee Implants – A Bonding Exercise

Even the most gifted surgeons have historically been limited by the accuracy of the saws available and no matter how well the knee components were cemented in place, they’ve always been limited by the nature of the cement itself – it inevitably breaks down over time. The bond between cement and bone is especially critical for patients who wish to return to athletic performance.

Even the most refined implants, matched as closely as possible to a patients’ anatomy, might stretch ligaments over time. Sadly, nearly half of all patients who’ve had total knee replacements report pain after ten years. All in all, partial knee replacement surgery has been one of the trickiest areas for orthopaedic surgeons to manage successfully.

Now, however, these risks are being rapidly diminished with the advent of ‘arm-assisted surgery’, which used advances in scanning, combined with ultra-sensitive haptic feedback to deliver even greater accuracy to orthopaedic surgeons – the ‘Mako’ system is coming.

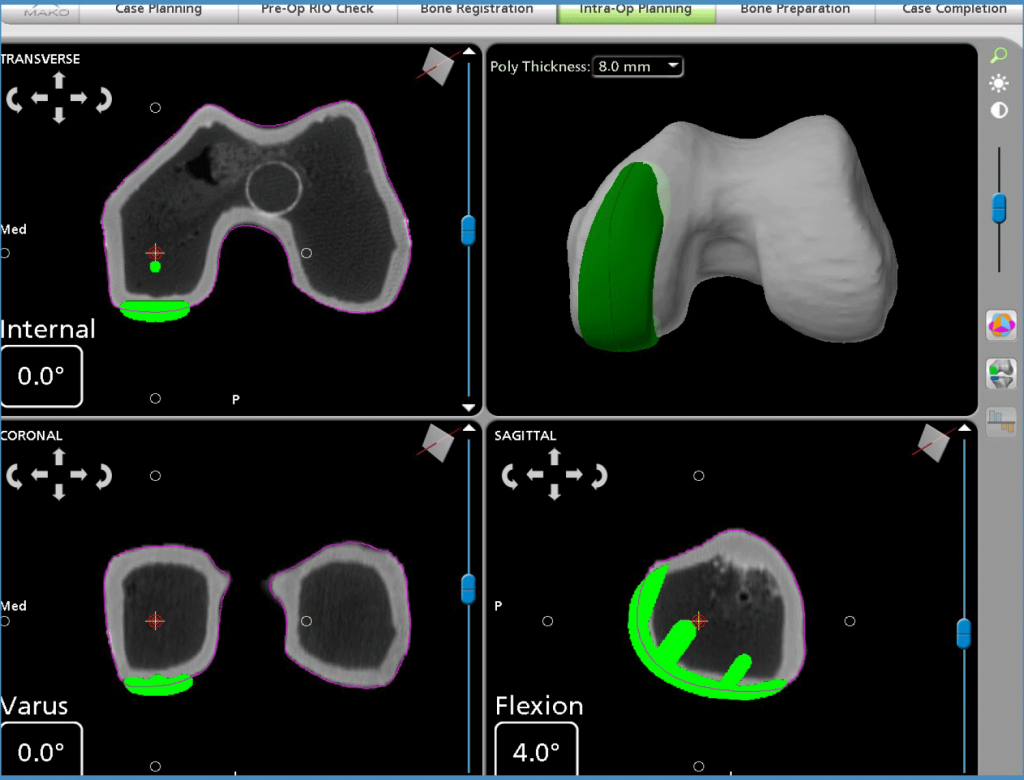

The Mako technology starts with an individual 3-D model to accurately pre-plan a surgical intervention. Using a CT scan and some clever software, the system ‘maps’ the individual knee and then facilitates the surgeon’s interventions according to the plan designed for each patient.

During surgery, the Mako system is guided by the surgeon, who receives haptic feedback (like the response when you press a key on your phone) to ensure the intervention is as accurate as possible. This enables the surgeon to remove only the diseased bone, preserving healthy bone and soft tissue, and assists in positioning any implant based on each patient’s specific anatomy.

During surgery, the Mako system is guided by the surgeon, who receives haptic feedback (like the response when you press a key on your phone) to ensure the intervention is as accurate as possible. This enables the surgeon to remove only the diseased bone, preserving healthy bone and soft tissue, and assists in positioning any implant based on each patient’s specific anatomy.

With robotic assistance, the surgeon can plan each patient’s care in advance with a virtual model of the patient’s own knee (built in 3-D from the CT scans). They can place replacement components virtually and adjust them to suit specific circumstances, before making only a small incision, resulting in the most natural knee motion possible.

A Surgical Balancing Act

During surgery, the knee ligaments can be balanced by rotating the knee and measuring its’ motions on a computer screen. The actual cuts are made by “driving” the saw with a robotic arm. The robot’s haptic controls don’t allow the saw to vary even slightly from the precise pre-planned cuts. The marriage of pre-surgical planning and actual ligament tension during surgery a huge advance.

Because of the increase in surgical accuracy, a cement bond between bone and the implant is often no longer needed. In fact, many new implants have patterns on their bases that, when perfectly matched to the bone, enable a fusion of bone to metal without cement.

That means that a partial knee replacement now has no need for saws, drills or guides. In fact, the procedure is now so minimally invasive that patients can often walk out of hospital an hour or two after surgery. Patients require significantly less anaesthetic. Physical rehabilitation can often be started the very next day. This offers significant benefits for patients, as well as significantly reduced treatment costs.

The Outer Limits of Knee Surgery

The results from partial knee replacement have now become so good that many patients are able to return to a full range of activities in incredibly short timescales. However, there are limitations too, often depending upon the range of movement in the first place.

By the time many patients ask for help, they’ve often had issues for some time. Muscles are often weakened, or hip and back mechanics have naturally compensated for the knee’s limitations and sometimes the range of motion may be quite limited. Extensive physical therapy and fitness work can help greatly, although they often require sustained commitment to return to athletic performance levels.

The rapid advent of the Mako system, combined with modern outpatient support and intensive physical therapy, is delivering outcomes for patients that seemed impossible even in recent years – many patients are skiing, climbing and participating in sports on partially-replaced knees at levels they haven’t managed in years.

In conclusion, robotic arm assisted surgery allows for partial knee replacements to be routinely performed by surgeons, thus not forcing the patient to suffer for years with a degenerative knee condition and be told to wait “until you absolutely have to” to perform a total knee replacement. The likelihood is, also, that more and more surgical procedures (like arthroscopies, shoulder surgery and cataract removal to name a few) are likely to be conducted in similar ways, delivering improved outcomes and reduced treatment costs for a multitude of different areas.

You can watch a detailed surgical demonstration (of a total hip replacement) using the MAKO system online here.

References:

[i]

http://jc.dalortho.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/robotic-assisted-uni-knee.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29983665

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5717071/